In March 2022, Sri Lanka experienced widespread unrest as a result of the government’s failure to contain the historically significant economic crisis. Now that the dust has settled, we can more clearly grasp and analyse the events and causes leading up to the crisis. In this article, Ananay Agarwal examines the economic causes of the problem, along with the most recent agreement between the IMF and Sri Lanka.

Sri Lanka formally went into default on its debt obligations in April 2022, which marks the official time-period when the situation went from imminent crisis to present crisis. The default immediately resulted in runaway inflation and a shortage of essential supplies like fuel, paper, and food. Shortly thereafter, the Sri Lankan public, frustrated with its political leaders, besieged the President’s Mansion in Colombo, leading to iconic images of crowds in the presidential swimming pool. This public outcry and anger forced President Rajapaksa to relinquish his office and paved the way for Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe to win the Presidency. As the economy gradually began to improve under Wickremesinghe, the most violent of protests had largely subsided by November 2022. As of writing, a path to resolve the situation and move the country forward has been constructed, and the path is being travelled upon, but the future is still uncertain.

Building up to the Economic Crisis: The Post Civil-War Boom

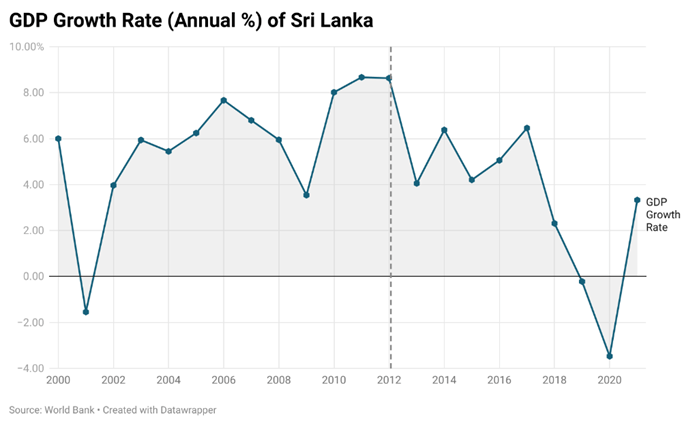

When Sri Lanka’s civil war came to an end in 2009, the country’s economy saw a substantial post-war boom. The economy started to show signs of life as the country’s infrastructure was renewed and security was strengthened. This boom, though, turned out be just temporary, and the growth could did not continue for more than three years. The graph below shows that by 2012, the GDP growth rate had dropped significantly, from over 8% to roughly 4% and never fully recovered to the highs of the early 2010s.

A small political elite emerged in the years following the civil war, controlling the economy and steering the nation away from pro-growth policies and toward personal gain. Foreign investments had dried up as a result of the conflict, and the new regulations established substantial trade hurdles for foreign corporations to invest in the nation as well as competitive barriers for new domestic firms to emerge without major political backing. Furthermore, with the Great Recession in full swing, prices for Sri Lanka’s two main exports – tea and rubber – saw a sharp drop in value, further depressing the post-war boom.

White Elephants

The term “white elephant” is used to describe a large-scale public investment project that is expensive to create and maintain, but does not produce sufficient economic returns or advantages to justify its cost. In the 2010s, Sri Lanka ended up opting for several such projects with funding from Chinese Banks. These include:

1. Hambantota Port: Located in southern Sri Lanka and funded by Chinese loans, the port was intended to act as a trans-shipment hub before the Malacca Strait. However, the project ballooned in cost, and the Sri Lankan government eventually handed control of the port to China on a 99 year lease. There were also several accusations of corruption, and many Sri Lankans even wondered if the port was ever required in the first place.

2. Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport: Also funded by Chinese banks, this Airport was opened in 2013 and intended to act as a second international airport to serve the capital city of Colombo. Initially many airlines did opt to use it, including Sri Lankan Airlines, but by 2018 all airlines had left. It was even dubbed the “World’s Emptiest International Airport” by Forbes magazine due to its low number of passengers and flights, and comparatively gargantuan size.

3. Lotus Tower: The tower is a 350 metres tall telecommunications tower, and has been criticised for its exorbitantly high cost and allegations of scams. Moreover, its location has also been questioned, with broadcasters saying that the tower neither covers all of Sri Lanka, nor improved the quality of current transmissions.

4. Lakvijaya Power Station: Sri Lanka’s largest power plant and accounting for nearly 15% of its tower power supply, the station has faced several breakdowns since its inception in 2011. It has been alleged that the government agreed to use sub-standard materials in its agreement, which might be responsible for its frequent failures.

2019 Easter Bombing

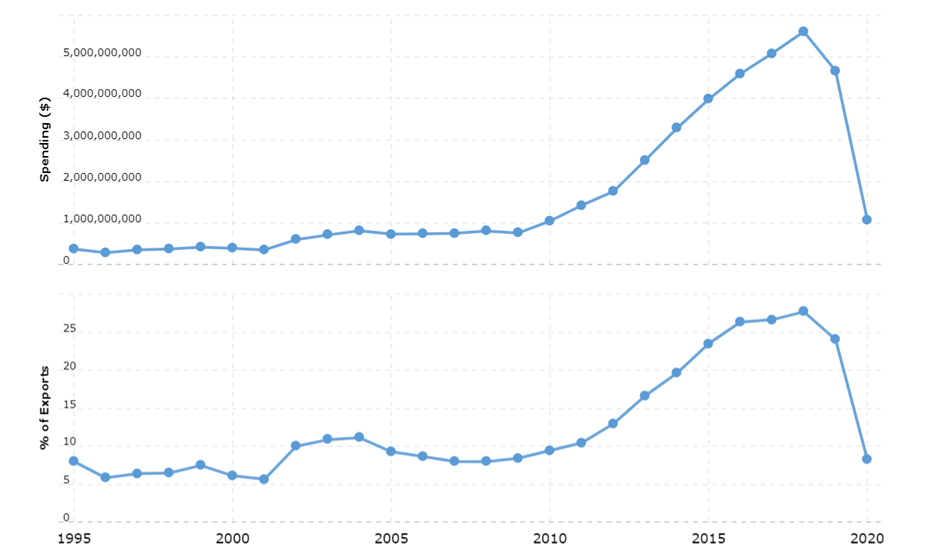

Over 250 people were killed in a string of Easter-related bombings in three churches and three hotels in Colombo in April 2019. Aside from the horrific loss of life and destruction of property, tourism – one of the main drivers of Sri Lanka’s GDP – immediately took a hit. Between 2018 and 2019, spending by international tourists decreased by 16.85%, and between 2019 and 2020, spending decreased by an extraordinary 76.92%. The below graph from MacroTrends shows very clearly that International Tourist spending – which in the 2010s was accounting for 20% of Sri Lankan exports – plummeted in 2019.

The decline in tourist arrivals also negatively impacted other sectors of the economy reliant on it like hospitality and transportation. The worst hit were self-employed individuals. Business that had hitherto been operating even during the worst phase of the Civil War were forced to shutter as tourists stayed away. GDP actually declined by 0.2% in 2019, owing chiefly to the Easter Bombings and subsequent Covid outbreak later in the year.

Covid-19 Outbreak

The outbreak of Covid-19 was an epoch defining event, and the world struggled to overcome it, with Sri Lanka being no exception. However, with an economy heavily reliant on tourists and the export of tea and rubber, the island nation’s economy faced an even bleaker time. In conjunction with the Easter Bombings, tourism completely dried up. Hundreds of businesses in Sri Lanka that cater to tourists were forced to shut down as the world went into lockdown and international travel ceased to exist. Additionally, as demand for its main exports declined, so did their prices, which negatively impacted its balance of payments. On the other hand, remittances from Sri Lankans living overseas decreased as more people lost their jobs globally.

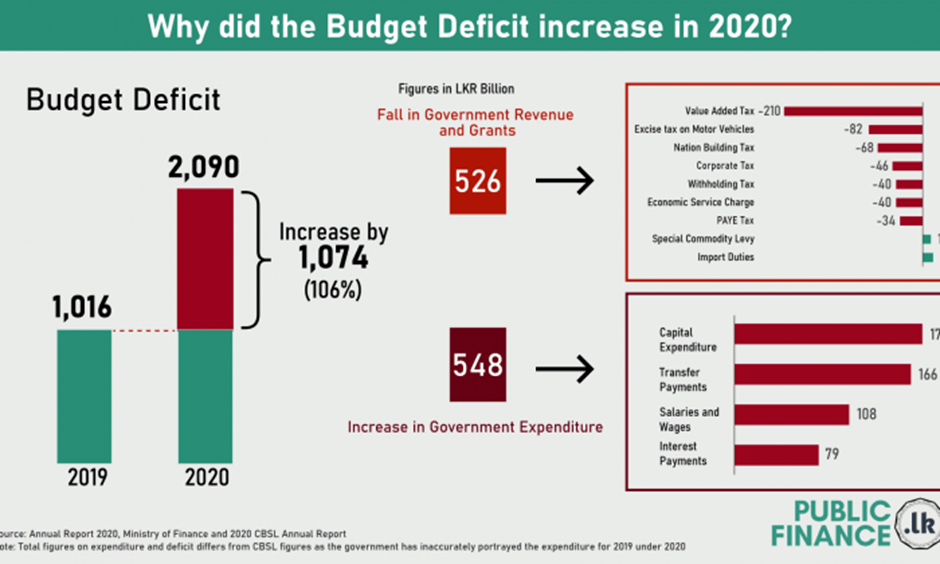

The pandemic also compelled the government to increase its budgetary expenditure and keep the economy from going down an even darker path. However, the incumbent Rajapaksa government had already slashed taxes in 2019 as a poll-promise, and this policy came back to bite them. The combination of falling revenues and rising spending caused the fiscal deficit to balloon to more than 10% in 2020. In hindsight, this was the first canary in the coal mine that Sri Lanka is in trouble.

Overnight Switch to Organic Farming

The final nail in the coffin was an almost overnight switch to organic farming. In a bid to address its balance of payments crisis, President Rajapaksa was advised that if the country stopped using imported chemical fertilisers, the import bill would fall and subsequently reduce pressure on foreign exchange reserves. The President began to position himself as an environmental champion and his country a haven for organic farming, and consequently banned – in one fell swoop – all chemical fertilisers from May 2021. Many environmental organisations applauded his decision and praised him as an example to be followed.

However, this policy had an extremely detrimental outcome. Farmers were left completely unprepared for the ensuing decline in soil productivity, having little to no notice to prepare them. Food scarcity resulted from the nation’s agricultural output falling to an all-time low and consequently, inflation shot through the roof. Ironically, this compelled the nation to import more food, undermining the very rationale behind this policy. In the end, a measure taken to alleviate pressure on forex reserves had the opposite effect and harmed them the most, serving as the proximate cause of the subsequent economic crisis.

Historic Dealings with the IMF

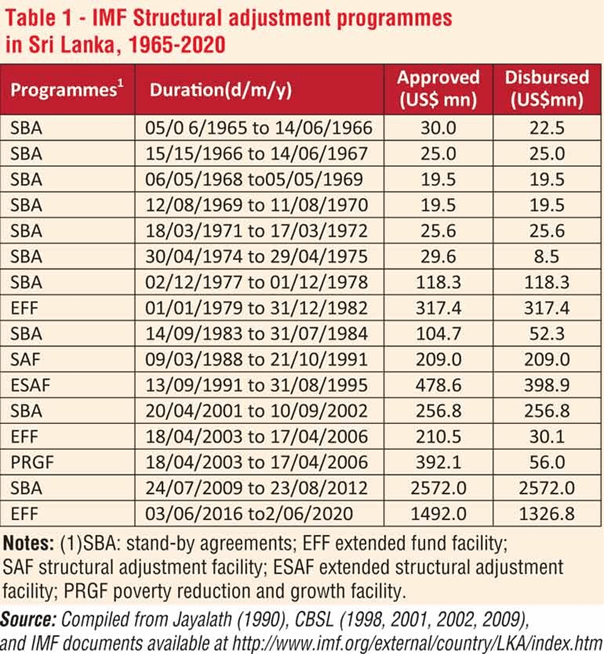

The International Monetary Fund and Sri Lanka have had extensive dealings since the mid-1960s. In the past 56-year period, approximately 33 years have been spent under the macro-economic management of the IMF, as shown by the graph below. It is to be noted that the IMF fully distributed the agreed funds under 12 of these 16 agreements, with Sri Lanka failing to meet the conditions for the full disbursement of the remainder.

The relationship between Sri Lanka and the IMF is multi-faceted and complex, and one should be careful to not attach simplistic “good” or “bad” narratives to both actors. The IMF, with its heavy ideological baggage of adhering to the Washington Consensus, did not always take into account the unique position of Sri Lanka’s geography or its institutions. Similarly, Sri Lankan politicians have always been quick to cast the IMF as a neo-colonialist entity and refused to implement policies that are unpopular in the short-term but beneficial for its long-term macro-economic stability.

Regardless of the narrative, the fact however is that the Sri Lankan economy has been running on a periodic cycle fuelled by unsustainable debt for decades. The debt is used to finance fiscal and current account deficits, an economic upturn occurs, and politicians kick the proverbial problem down the road to the future generation. Invariably, when the global economy coughs and debts are called in, Sri Lanka catches a cold. The country has unfortunately followed a pattern where it sets out onto the path of fiscal reform to stabilise its economic system, but then reverses direction and fall back into crisis.

The 2023 IMF deal

On March 20, 2023, the IMF and Sri Lanka signed an Extended Fund Facility (EFF) agreement to help bring the country out of its economic quagmire. The 48-month arrangement will infuse capital into the country’s coffers and allow it to pay for necessary imports like food and fuel. This should give enough policy room to the government led by President Wickremesinghe, to implement structural changes in the economy. The President has also stated the EFF should help increase confidence in the country’s economy and allow the government to access another 7 billion USD in funding from other multilateral and international creditors. The IMF immediately released 0.333 billion USD in funds, with more expected to be released in the following months.

What is an EFF?

The EFF, or Extended Fund Facility is one of IMF’s several financial assistance programs, with others being the Stand-By-Arrangement (SBA) and Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI). The choice of program the IMF chooses to utilise depends on the specific needs and problems of the country in question. The EFF is designed to support countries that are facing a balance of payments crisis. It is aimed at helping countries implement long-term structural reforms in their economy so that underlying macro-economic difficulties can be addressed. Under this program, the country in question receives financial assistance in the form of loans or credits for three to four years from the IMF, but with several strings attached. The recipient country is typically required to pass reforms that are aimed at restoring macro-economic stability, reducing fiscal deficits, improving tax collections, reduce government expenditure, and increase productivity and efficiency of state institutions.

The official IMF statement has identified four key areas in which reforms are to be implemented – Tax Administration, Public Financial and Expenditure Management, Energy Pricing, and Anti-Corruption Legislation.

Tax Administration

The last three IMF programs, in addition to the new one in 2023, have primarily focused on addressing the low tax collections of the Sri Lankan government. In December 2019, the government slashed indirect taxes like Value-Added-Taxes (VAT) from 15% to 8%, and the corporate income tax rate from 28% to 24% as poll promises. In addition, other taxes like the nation-building tax of 2%, the Economic Service Charge and PAYE, were also abolished. As a result, Sri Lanka had one of the lowest revenue-to-GDP ratios in 2021. Total tax revenues fell by over 520 million LKR between 2019 and 2020, i.e. nearly 30%.

On the flip side, Covid-19 and the Organic Farming fiasco caused an increase in government expenditure by nearly 550 million LKR. This included things like Covid relief assistance through the State Ministry and recruitment of 160,000 unskilled an unemployed graduates. Together, the budget deficit rose by over 100% between 2019 and 2020.

The IMF has strongly urged Sri Lanka to implement “progressive” taxes, i.e. charging more tax from the rich, instead of “regressive” taxes, i.e. charging more tax from the poor. Indirect taxes are strongly regressive in nature, since they are taxes paid on the consumption of goods and services. Hence, regardless of income, consumers pay the same tax, implying that poorer people end up spending a greater portion of their income on indirect taxes than wealthier individuals. By adopting more progressive taxes, Sri Lanka should ideally shift away from its heavy reliance on indirect taxes (over 80%) to more sustainable sources of tax income.

Public Financial and Expenditure Management

The IMF has effectively asked the Sri Lankan government to “tighten its belt” so to speak. It should spend only within its means and cut down on its deficit. A big part of this involves restructuring its external debt obligations from other multilateral and international creditors. This might be in direct reference to the several white elephant projects the country has invested in, many of which have been more hassle than benefit. Sri Lanka needs to consider its long-term finances and act judiciously instead of impulsively funding projects without considering its costs and benefits.

Energy Pricing

Sri Lanka is significantly dependent on fuel imports from abroad because the country does not possess a significant endowment of hydrocarbons. As a result, supply and demand dynamics on the commodity markets determine energy prices in Sri Lanka. With the Russian-Ukraine war, the cost of coal and oil increased, and Sri Lanka had to pay more to maintain its fuel supply. In order to maintain fuel imports and the island’s supply of electricity, the Sri Lankan government started using up its foreign exchange reserves of USD at an unsustainable rate to continue buying fuel in the international market. Eventually, this was no longer feasible, and a decline in resource imports brought about national fuel rationing and electrical shortages.

This fuel rationing and electrical shortages made it clear that Sri Lanka and its citizens were at the mercy of uncertain international energy markets. Since the country imports nearly two-thirds of its fuel, the IMF wants Sri Lanka to diversify its energy sector away from hydrocarbons. Shifting to green and renewable sources of energy like wind, solar, or tidal will ensure a more stable supply of electricity to the country and also decrease the pressure on its foreign exchange reserves.

Anti-Corruption Legislation

The IMF has praised the ongoing efforts of the country in tackling corruption, and asked that they continue and ultimately culminate in revamping anti-corruption legislation. The IMF will also continue conducting the governance diagnostic mission that will assess Sri Lanka’s anti-corruption and governance framework.

Such governance diagnostic studies have recently been conducted by the IMF in Moldova, the Republic of Congo, Mauritania, and Zambia. The reports on the Republic of Congo, Zambia, Moldova, and Mauritania are all available online.

The IMF believes that these analyses are instruments that nations may employ to build strong governance structures and strengthen the rule of law. In all four nations, the IMF teams examined the central bank’s governance, the financial and fiscal sectors, the protection of property and contract rights, the tax system, and anti-money laundering systems. It seems clear that the diagnostic framework on Sri Lanka will look at the same items given the press briefing released by the IMF.

The diagnostic framework however has been heavily criticised due its strong ideological tinge in neoliberal economics, and been called a propaganda tool to legitimise austerity. The fact that the Sri Lankan government has currently authorized the sale of a number of profitable State-Owned Companies is particularly pertinent to notice. This choice has most likely been made under pressure from the IMF that believes that governments shouldn’t become involved in business. Regardless, the authorisation of these sales encouraged strikes by labour unions and in turn triggered the outlawing of strikes by the government.

Conclusion

With the benefit of hindsight, it is not unreasonable to say that the current crisis is a repeat of a historical pattern that has regularly played out in Sri Lanka. This time however, the crisis has been particularly acute and there is a very real chance that Sri Lanka can veer off its debt fuelled trajectory. The way forward for Sri Lanka lies in making imperfect policy choices.

Firstly, significant hikes in taxation, particularly indirect taxes like VAT, will disproportionately affect the poor and less well-off, at a time when they are already facing the brunt of the crisis. However, high tax collections is one of the conditions that the IMF has imposed, and indeed greater revenue will certainly create a healthier economy in the longer term. Secondly, the government must also spend only within its means, but this will certainly reduce the societal benefits it provides to its citizens. It is thus unclear how Sri Lanka will accomplish the IMF’s simultaneous demands for “expenditure management” and an increase in social benefits. Thirdly, diversifying away from hydrocarbons to green energy might sound good on paper, but has the potential to make Sri Lanka even more reliant on weather patterns and the monsoons, since these will then directly affect its energy production. Lastly, while corruption is a menace in Sri Lankan society and certainly needs to be combatted, there is a case to be made that the IMF is no moral superman, and its diagnostic framework a tool to legitimise its authority and ideology.

The most likely conclusion is that Sri Lanka recovers from the crisis “better than before,” with the likelihood of the two extremes—reverting to previous behaviours or becoming a wholly different Sri Lanka—being far lower.

Suggested books for in-depth reading on this topic:

- Economy, Culture, and Civil War in Sri Lanka (Deborah Winslow & Michael D. Woost (Eds))

- The Cage: The Fight for Sri Lanka and the Last Days of the Tamil Tigers (Gordon Weiss)

- The Seasons of Trouble: Life Amid the Ruins of Sri Lanka’s Civil War (Rohini Mohan)

Additional geopolitical reading suggestions can be found on our 2023 reading list

Purchases made using the links in this article earn referrals for Encyclopedia Geopolitica. As an independent publication, our writers are volunteers from within the professional geopolitical intelligence community, and referrals like this support future articles. Encyclopedia Geopolitica readers can also benefit from a free trial of Kindle Unlimited, which offers unlimited reading from over 1 million ebooks and thousands of audiobooks.

Ananay Agarwal is a graduate of Delhi University and holds an Economics masters from the Institut d’études Politiques de Paris (Sciences Po), and specialises on the modern and historical geopolitics of India and South Asia. He has collaborated with some of India’s most eminent academic researchers and parliamentarians on public policy, economic, and political matters. Currently, Ananay is continuing his research at the Indian School of Business.

For an in-depth, bespoke briefing on this or any other geopolitical topic, consider Encyclopedia Geopolitica’s intelligence consulting services.

Photo: Vyacheslav Argenberg